Dr. Daryoush Tavanaiepour Interim Chair, Department of Neurosurgery, Medical Director, Skull Based Surgery, Assistant Professor of Neurosurgery, University of Florida

Dr. Daryoush Tavanaiepour Interim Chair, Department of Neurosurgery, Medical Director, Skull Based Surgery, Assistant Professor of Neurosurgery, University of Florida

Dr. Tavanaiepour works at UF Health College of Medicine in Downtown, Jacksonville, and he was so kind as to set aside some time out of his busy schedule, to receive us for a casual interview.

When did you first decide you wanted to become a doctor?

It was towards the end of my undergraduate at the University of Pittsburgh. I was studying neurosciences, and was fascinated with how the brain worked. It was during that time period that I wanted to go to medical school.

What school did you attend?

It’s called University of Otago, in New Zealand. My wife is from New Zealand, which is why I chose to attend school there.

Where did you do your medical residence?

I came back to the United States and went to the Medical College of Virginia, in Richmond. I think the formal name now is the Virginia Commonwealth University School of Medicine.

Why did you choose that one?

I went there because it was a very good program, and I knew that I would get excellent training. The school performs many surgeries and has good professors. I knew I would learn a lot from them.

What surprised you the most while you were in medical school?

The diversity of students, from all over the world was very exciting to me. I also remember sitting in class on the first day, wondering: “how are they going to teach me how to become a doctor?” The real question was: “how am I going to become a doctor?” To me, they provided information that allowed me to learn and to become a doctor.

Did you find it hard?

Oh, I loved it! I really enjoyed it. It was a lot of work, but I really loved what I was studying. It was exciting.

When/how did you know neurosurgery was the right path for you?

At the end of medical school, I knew I wanted to do something related to the brain because of my previous degree in neuroscience, and it was either psychiatry, neurology or neurosurgery. I was very impulsive, one day I was walking by the office of a neurosurgeon. I don’t know how it happened, it was very random, not planned. I knocked on the door and the doctor was there. I had a conversation with him about neurosurgery. Soon after, I ended up doing a rotation with him, just to see what it was like. That’s how I knew I wanted to be a neurosurgeon.

So, it was like your calling, something you were meant to do?

Now I can say that, but at the time, no. It was very random, like “hey, you’re a neurosurgeon, a doctor, and I’m a medical student.” I did not have the intention of becoming a brain surgeon when I went to med school, no way! I did not think that. I kept an open mind and I was heading down the route of brain problems, either psychiatry, or neurology, but neurosurgery came out of nowhere. I wasn’t expecting that.

Has neurosurgery met your expectations?

Yes. I would say it is not a job; it’s a way of life. It’s extremely demanding, and very hard. At the same time though, it’s my passion. I wouldn’t do anything different.

What do you like the most about being a neurosurgeon?

The challenge, and helping patients who have no place else to go. Especially, if I see a patient who tells me that the prior doctor said “there is no hope, there is nothing else we can do for you.” That gets me more excited to prove them wrong.

Have you succeeded in those hard cases?

Yes. Somehow I have created this niche where I am getting very complex cases coming to me, I don’t know how, but they are, and I try to do what is best for the patient.

What do you least like about being a neurosurgeon?

I really, really love what I do. It’s not about neurosurgery, but about being a doctor in the United States. What I don’t like is that money and insurance play a role in healthcare.

In your position now, knowing what you do, what would you say to yourself when you were beginning your medical career?

One thing that happened recently, during this past year that I did not expect to happen, was to take a leadership role. A leadership role requires a lot of other skills that you do not learn in medical school; mainly, how to be a good leader, how to understand administration, financing, and marketing. All those skill sets were not provided in med school or in residency. If I knew that, I would have taken formal training in health administration or healthcare financing.

What top 5 surgeries do you do most often?

Spine surgery is very common. I do that a lot and there are different types of spine surgery, in the neck or in the back. There are people who get injured from trauma that need spine surgery, and patients who come to you because they have arthritis or degenerative problems of the spine. For me, the most common things I also do are brain tumors obviously, and another field called Deep Brain Stimulation, where you place electrodes in the brain to help patients who have Parkinson’s Disease or tremors. It’s like a pacemaker for the brain, so the DBS and brain tumors are my most common things, followed by the spine.

What type of surgery do you like to do the most?

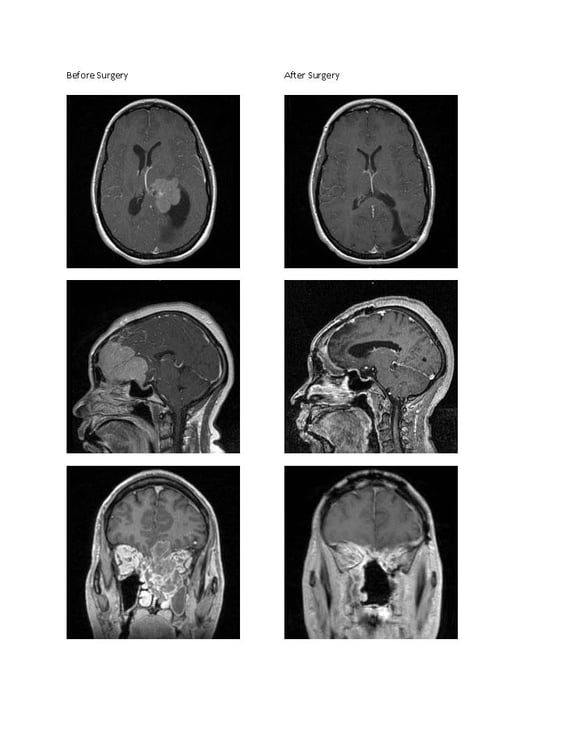

Complicated brain tumors because of the challenge. The ones that others say “Oh, you’re not operable.” It’s very stressful, and I spend days if not weeks preparing. Then afterwards, when the patient does well, it’s so rewarding it makes me want to do it again. So that’s what I would say about complex brain tumors. I enjoy doing those. I’m scared to say that! It’s like, why would you like something so stressful? But I do. The other part that I really enjoy is Deep Brain Stimulation, placing electrodes in the brain, the pacemaker. You really help patients who can’t do their daily activities because they have tremors, and they are slow and rigid from Parkinson’s or tremor disorders. This technology that we use in the surgery really helps them. It is rewarding.

What is the most challenging surgery you’ve done?

One of them, to give you an example (gets up and looks for a plastic skull on a shelf), this is the actual skull of a patient, the model of someone’s head. You look at the eyes and the nose, and the top of the head is off. When you look in here you see this big, round thing here?

Yes.

That’s big tumor, a giant tumor. Think about how big that is if compared to your skull. And this line here, and this other line going through here? That is a major artery that is stuck to the tumor, (points and shows all details as he speaks). And what happens is, it goes further back and it’s pushing on the eye nerve, so he could be going blind because the eye sockets are here, and the nerve goes back. But, as it is going back, the tumor is pushing down on it. So, I think the most complex tumors are the ones called Skull Base Tumors. They are at the bottom of the skull where the head meets the neck, and it’s a very complex anomaly, and those are the most complicated ones.

The skull base is one of the most complex anatomical regions of the body and one of the hardest to reach surgically. As its name suggests, this is the part of the skull which supports the brain and where the eye sockets, nasal cavities and ears connect to the brain. Tumors in this area can be some of the most difficult to treat because of the delicate structures surrounding it. Those structures include blood vessels and nerves which can affect speech, smell and eyesight. *Image and text used with permission.

Do you choose your own surgery settings and staff?

Well, the hospital hires people, but we’ve created a team. I really do want to make a point that, in these surgeries that I do, my team is extremely important. The scrub nurse, Val, is the one who works with me in instrumentation while I’m operating. She’s absolutely critical, I can’t thank her enough; and also Manoj, who is the nurse in operation while I’m running around getting equipment and so forth, he’s been extremely helpful, and I quite often thank them. Afterwards, they don’t know, so I tell them: “Hey, the patient that we operated on yesterday is doing great,” so they are now part of that team, and they understand the complexity of it. It is really important, because those two people know me, so they know when I am too stressed, and something is going wrong, or when I am relaxed, or what I need, and how I do things in my routine. Otherwise, if every day there is somebody new, they won’t know our procedures, especially in complicated cases. I think it is sad they don’t get recognized enough, because they are hugely valuable to me. I want them to get acknowledged for that.

Are you particular about the instruments that you use?

Particular is a good word, (laughs) maybe extremely particular is even better! Because, as you can imagine, in those kind of surgeries, and how delicate they are, the instruments are hugely important. When you’re under the microscope, looking through things, they magnify, and you’re looking at a tumor, and a vessel, and you’re trying to tease it out, having appropriate equipment is very valuable. That is when my staff, Val, comes in. She opens all of the equipment in the morning, and looks to make sure all the right things are there even before I come in the room. Sometimes, equipment might be missing or maybe the scissors are dull. That’s where the other staff comes in and they can try to repair things or replace them. Yes, a surgeon’s tools are very important.

Do you personally choose those instruments? If yes, why?

When I first came here, yes, I made requests to the hospital on what equipment I needed to do these complicated cases, and those were purchased based on my recommendations.

Do you use disposables at all?

Yes, we do. Disposables are a tricky situation. I think that they have a lot of advantages, and I will give you an example later on. However, what I hear is that they’re more expensive. For example, if you buy a scissors, micro scissors for example, the cost is less, because you purchase them once and use them many times. As time goes by those scissors will get dull, and I want them to be perfectly sharp. Ultimately you can say: “Well, now it’s dull, buy me a new one.” That’s one approach. The other approach is to say “well, no, this is so critical that every time, this instrument needs to be perfect,” and that’s where disposables come in.

What are the benefits or advantages you see in using single-use instruments in neurosurgery?

The value of disposables is that you are getting the equipment at its best. There are certain times where I want that and will request disposables. Most of the time if I can get without needing disposables, thereby saving the hospital some money. Bipolar forceps are a good example. You grab things and then push a button to run a current that stops the bleeding. So, with a tumor, you get the bipolar, and make it shrink and the blood supply dies. Disposables are very helpful for that, because they are designed for it, they do not stick to the tumor. Reusables are more likely to stick to the tumor. The first couple of times maybe it won’t stick, but as time goes by, if you keep on using it, the surface has a coating that prevents it from sticking, and after a while that might wear off and start to stick more often. Again, I don’t advocate that everything has to be disposable. There are certain instances where it’s ok not to use disposables. There are some critical things, especially when it comes to brain surgery and tumor removal, where disposables make sense, even if it’s more expensive. For example, a knife, you want it to be sharp all the time, or the bipolar.

From your perspective, what is the biggest problem in healthcare today?

The frustration is some patients have restrictions due to financial issues. If I need a certain test, or I need to do a certain procedure, the insurance company might say “no” and you end up needing a lot of phone calls and paperwork to get something approved. I think that’s the biggest concern.

What advice would you give to students who aspire to be in neurosurgery?

There is no way that you can survive neurosurgery unless you are truly passionate about it. The lifestyle of a neurosurgeon is very difficult, the training is very difficult, the type of patients you see are very challenging and it’s very demanding. Unless you have that fire, or that passion, it won’t be worth it. You have to ask yourself if the passion is there, otherwise, it’s not worth the commitment.

Sklar is proud of its fine line of surgical instruments. You may click the link below to browse through our high quality neurosurgical inventory.